In my field, the assessment of learning differences, I find that I am often alone in asserting (strongly) the limitations of neuropsychological evaluations. So much so that I am pursuing an educational psychology doctorate to confront the institutional barriers of identification of those who have learning differences. With a doctorate in psychometrics, it is my hope that I come across as a voice of authority in the limitations of testing—not as a proponent of testing!

In my field, the assessment of learning differences, I find that I am often alone in asserting (strongly) the limitations of neuropsychological evaluations. So much so that I am pursuing an educational psychology doctorate to confront the institutional barriers of identification of those who have learning differences. With a doctorate in psychometrics, it is my hope that I come across as a voice of authority in the limitations of testing—not as a proponent of testing!

Every student of psychology who learns about testing must also learn the following:

Every student of psychology who learns about testing must also learn the following:

• Testing is limited.

• It is hazardous to generalize testing results, generated in an artificial test environment, to real-world experiences.

• Testing is limited.

• Modification of tests, especially for those with learning needs, is common; yet, we do not quite know how modifying tests affects the results.

• Testing is limited.

• Known and unknown factors may affect testing results in known and unknown ways.

• Testing is limited.

• The historical pattern of behavior of learning diffiuclties trumps the results of a standardized test—every time.

• Testing is limited.

Despite cautionary tales and directives from the APA and the Standards, it has been my experience that school psychologists, psychologists, and diagnostic centers become, by-and-large, over-reliant on the statistical “evidence” of their standardized tests and the real opportunity to help is lost. This over-reliance on neuropsychological evaluation for diagnostic certainty is appalling—and I believe it is undermining our society. I witness the practical applications and benefits of testing daily; yet, I believe that the “missed” perspective—the perspective that testing is quite limited—renders most with learning disabilities undiagnosed.

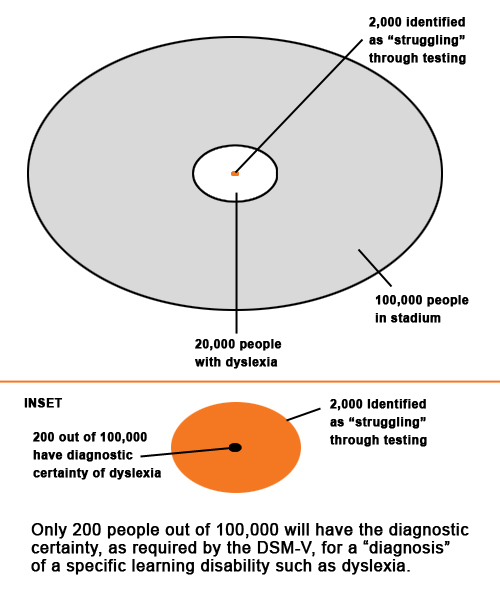

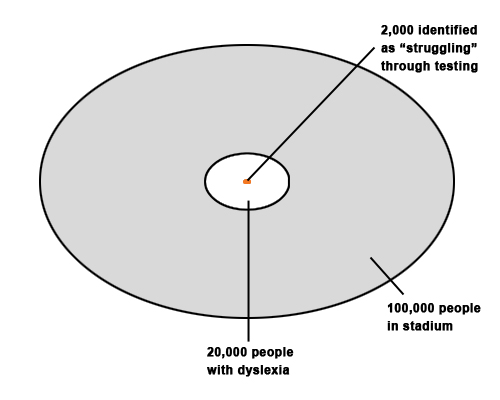

Statistically speaking, if you have a stadium filled with 100,000 people, then 20,000 of those people will have dyslexia. Of those 20,000, only about 2000 will be identified as “struggling” through testing. Yet of those 2000, only 200 will have the diagnostic certainty, as required by the DSM-V, for a “diagnosis” of a specific learning disability.

This means that 18,800 of those 20,000 with dyslexia will never be identified in a way that will give them access to services. Yet our educational systems insist that we only identify these children through standardized testing!

This means that 18,800 of those 20,000 with dyslexia will never be identified in a way that will give them access to services. Yet our educational systems insist that we only identify these children through standardized testing!

And we wonder why we as a nation have a functional literacy rate of 57 percent! Forty-three percent of Americans read at no higher than a 3rd grade reading level—and even then, they need context clues. Inadequate literacy in our country has extremely high correlates to poverty and prison.

Regularly, we encounter students who have languished for years after being misdiagnosed or undiagnosed by someone (mis)using a neuropsychological battery, in a contrived setting, with limited interpretation. In learning disabilities assessment, the Golden Rule is this: The pattern of behavior, the historical intake, is more revealing and can trump a neuropsychological evaluation. A neuropsychological evaluation is done to provide supplementary evidence—but is not evidence in and of itself. A neuropsychological evaluation can be helpful—but it is not definitive.

Connect with LexiAbility

RSS

Facebook

Twitter